My Bulletproof Vest

“Most bulletproof vests won’t stop a knife — you need a special metal plate for that.”

Vinny from Atlantic Firearms in Baltimore couldn’t understand.

“And you’re a teacher?”

Visiting my girlfriend on McMechen Street over April break, I’d hear the snap, crackle and pop of fireworks throughout the night. Fragments of lead ripping through windows of surrounding buildings. Guns fired skyward. Gangbangers showing off, if not sounding off.

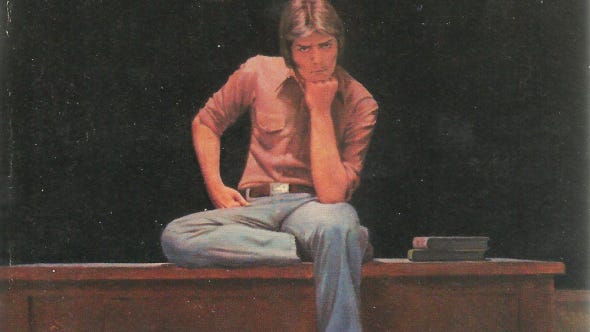

But I wasn’t worried about getting caught in the crossfire, being a bystander in a drive-by, watching a turf war unfold like a deleted scene from The Wire. It was going back to Massachusetts that concerned me - back to my classroom with big windows that overlooked the quad - back to a tiny HS with six English teachers - where I was the Drama director - where students played hooky on opening day of hunting season - where each morning I’d watch my students carry long black locked cases containing not flutes or saxophones or violas - but loaded rifles and handguns.

I wanted a bulletproof vest to give myself a competitive advantage. Or maybe it was just an adult security blanket. Or - even still - a grand act of self-delusion.

Not that my larger-than-average head would be spared, or my extremities, or lower parts, but at least most of my vital organs would be unscathed in the event of a school shooting.

And this was years before Matt, a senior I was working with on the speech and debate team, would frequent the school psychologist’s office and talk about “Mr. Phillipson” and “my gun,” in the same sentence.

It was before Harris and Klebold would decimate the same HS that the creators of South Park attended in Littleton. They’d throw pipe-bombs into the school cafeteria. Pipe-bombs they’d made in their parent’s 3-car-garage, unnoticed, unsupervised. Uncared for.

And, most powerfully, it was decades before there would be a mass shooting in America every 2.5 days.

I hung up with Vinny and ran my finger down the Yellow Pages section of “G for Gun Shops.” Isn’t it interesting that when we badly want to solve a problem we go about solving our problem badly?

How many gun dealers would have to tell me that they could only sell bulletproof vests to law enforcement before I would take no for an answer? That night, just outside Baltimore’s inner harbor, I listened to the sounds of urban warfare, instinctively clutching my viscera, then my heart, then resting my hands on my throat. I wondered what my young shooters were up to: those freshman boys who carried their .22s from the school bus to their locker to the range after school.

Did they have visions of taking down majestic bucks in the thick brush of Western Massachusetts? Did they find rapture in the rupture — the life draining out with each drop? Did they dream about their guns? Sleep with their guns ready, accessible, on the nightstand, stood up in the corner by their bedroom doors?

The school psychologist would tell me, in 1999, that Matt was talking about me and his gun a great deal in the same breath, and that she probably shouldn’t be telling me, but she really thought I should know.

Kurt would draw blood-soaked hunting knives on his handouts and leave them on his desk at the end of class. Were they for me to see?

When I “outed him” to that same counselor, his confrontation with me later that week, after class, standing over my desk with his spiky blonde hair that seemed strangely appropriate for everything I understood about him (which was nothing) was:

“What did you think I was going to do?”

And my answer was, and still remains, I don’t know.