My Neighbor, Don DeLillo

{He could be Mel Gibson’s body double in the original Mad Max, but he’s really just a failed dentist and Nobel shortlister for Literature.}

I’ve been in the same room as Don DeLillo, just not at the same time. And “to enter a room is to agree to a certain kind of behavior.” In this instance, I’d set the terms.

It was to happen in the doorman’s “break-room” at The Doyenne* apartment building in Bronxville (technically Yonkers, but the zip code remains the same). It’s a half-dozen stories, put up in the mid 1930s, with Art Deco flourishes that begin and end with its lobby.

Doorman John Folkes would sometimes save a parking spot for me (we’d swap cars at the end of his shift; I’d be extra generous come holidays), but between signing for residents’ packages and walking a Schnauzer or two, he’d also acted as the go-between for Wes Phillipson and Don DeLillo.

My written appeal to the National Book Award winner (among other PEN nods, and a near Pulitzer for Underworld) was simple enough, but thoughtfully constructed:

“I have two complete collections of your first edition novels and plays that I would truly appreciate having autographed by you. If you’re willing, I’ll leave them with my doorman for you to sign at your convenience. We’ll never have to cross paths. My understanding is that you live across the street.”

There was more to the letter than that, of course, and it wasn’t our first time communicating.

{Bronxville’s Doyenne* from the back lobby entrance point of view — whiffs of Bertie Wooster’s digs, with notes of Cloud Club foyer abound.}

I had never heard of DeLillo before coming to teach at Scarsdale. Two colleagues of mine sometimes assigned White Noise to their advanced classes, or added it to their research paper book rotation. It’s a mid-80s angsty meditation on how media and technology are undoing us, but it’s well disguised as disaster porn and character study. It may be the author at his most prescient — pointing towards a near future landscape dotted with interfering Alexas and Echoes, ambiguous lifestyle drug adverts, and a generalized dissociated way of moving through one’s privileged and mechanized world. DeLillo writes of people self-relegated to information silos before “echo chambers” was even a term of endearment.

White Noise follows a Hitler Studies professor through a litany of his worst fears come to pass, as he holds fast to (and literally clutches) a hardbound copy of Mein Kampf as a life-preserver-meets-security-blanket. Jack Gladney is invisible without his uniform (black graduation robe), and adrift without his perverse self-help Bible. The novel is set in the fictional midwestern town of College-on-the-Hill, but it’s undoubtedly a proxy for Bronxville’s Sarah Lawrence College.

In a Searching for Sugar Man moment, one English department colleague of mine from Scarsdale High School would sometimes exit the train at Bronxville Station (on his way home to Inwood), with just the vague notion of “spotting DeLillo,” as if he weren’t a Blue-crowned laughingthrush in a Yulan Magnolia.

Bronxville is one square mile, so size was on his side. A dignified salt-and-pepper head, inscrutable and otherwise anonymous, would surely - eventually - emerge from the rush hour crowd.

When I tracked down DeLillo’s address on a free people-finder website in 2006 (or thereabouts), I wasn’t yet plugged into Google Maps — which had just launched into public consciousness anyway.

I’d come to learn that his home was .3 miles* from The Doyenne by car, but a mere kitty-corner on foot.

The friend who’d told me that DeLillo would “never respond” to my humble epistolary approach was skeptical even after I’d thumbtacked Don’s postmarked, handwritten envelope to his office cork-board.

DeLillo types everything (except when he writes on envelopes). And I don’t mean “type” the way we use it colloquially. No. I mean he uses only one machine: an Olympia SM 3.

The letter’s concluding sentence to me read: “Currently, I’m being stalked by a novel day and night, but I’ll do my best to respond to your students’ questions in the time available.”

About two weeks later I’d received five typed pages, half-spaced, with some hand-done corrections. And while I can’t quote (or even paraphrase) from those pages because I was warned by DeLillo that “these remarks are for classroom use only and not for circulation elsewhere,” I can say that much of what was contained in the letter was both surprising and conceptually abstract. The sentences were breathtaking or - conversely - life affirming.

Phrase-making must be effortless, second nature, or just an internal-set-of-rhythms-made-public for DeLillo.

Despite my students’ thoughtful White Noise questions having been answered, I wanted more from him.

And that was likely the problem.

Don DeLillo may someday win the Nobel Prize. If Hemingway got one in spite of publishing The Fifth Column and Across the River and Into the Trees, and later work that tanked (save for The Old Man and the Sea), then DeLillo has more than earned his with Underworld and White Noise alone.

The New York Times surveyed working authors in America ten years ago, asking which “peers” they most respected, and the landslide winners were:

Toni Morrison

Don DeLillo

So, I wanted to get a bit closer to understanding the mind that could generate such sentences as:

“The family is the cradle of the world’s misinformation. There must be something in family life that generates factual error. Over-closeness, the noise and heat of being. Perhaps even something deeper like the need to survive.”

And:

“There’s a neat correlation between the complexity of the hardware and the lack of genuine attachments. Devices make everyone pliant. There’s a general sponginess, a lack of conviction.”

DeLillo’s sentences are like declarations of unknown truths that you have to feel your way through, abandoning any hope of understanding them so as to one day explain them to someone else.

Each DeLillo sentence is its own Christopher Nolan film. Right now I’m reminded of the scene in Tenet when the protagonist (literally named The Protagonist), tries to understand entropy’s impact on bullets that have already been fired in the future. The lab-coat scientist gives a quiet look of empathy and says, “Don’t try to understand it. Feel it.” His response: “Instinct. Got it.”

I teach White Noise (when I do), as a work of satire. I do so with the intimate knowledge that it may not actually be a work of satire at all.

But I’m in it for the sentences. It’s the same reason I teach The Great Gatsby. It’s not necessarily a great story. Just as Saltburn isn’t much of a narrative (just an unimaginative reimagining of Fitzgerald’s “Diamond as Big as the Ritz” meets Highsmith’s Ripley). White Noise has no traditional narrative arcs - if any at all. As a story, it plods along and suddenly explodes. Sometimes there is set-up and punchline, but often there’s only entropy.

While each Fitzgerald sentence is a pyrotechnic grand finale, DeLillo sentences read like fortune cookies written by a Washington D.C. think tank, or diction and syntax lifted from the internal memos of a nefarious agency: a cross between the manifesto for The Parallax Corporation, and an encrypted email Jeff Skilling once hypothetically sent to Ken Lay — in code without a cipher.

And you won’t find that kind of writing anywhere else in prose fiction.

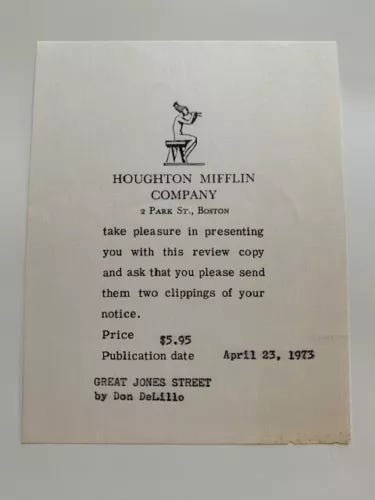

Months after DeLillo had signed both my copies of Amazons (a faux-hockey memoir by the “first professional female player” pseudonymously written as Cleo Birdwell), Great Jones Street, End Zone, and three big boxes containing his 18 novels and 10 plays (x 2), I’d sent off another missive to my famous neighbor at the local post office, offering him my set of Matthew Barney Cremaster film cycle on DVD (after seeing DeLillo had written a review of Cremaster 5 years prior).

A pop-art postcard in that tight, inimitable scrawl, appeared in my letterbox days later. He’d declined my offer.

But my fleeting connection with DeLillo had been long-ago launched with the offer of another gift: an uncommonly autographed copy of a Zbigniew Herbert book. Herbert was an obscure Polish poet and essayist that DeLillo had dedicated one novel to (Underworld, I believe), and whose poetry had found its way into another novel (Cosmopolis) like a 1-877-Kars-4-Kids earworm. As The Guardian’s Betsy Reed wrote in an editorial:

“Cosmopolis' 28-year-old fund manager contemplates his financial ruin. And the poem that keeps running through his head is Report From a Besieged City by Zbigniew Herbert. It is part chronicle - "Monday: stores are empty, a rat is now the unit of currency." - and part hymn to desolation: "We govern ruins of temples, ghosts of gardens and houses / if we lose our ruins we will be left with nothing."

Very much unknowingly at the time, I’d mailed DeLillo a Herbert signed and dated the very day that DeLillo himself had looked at The Twin Towers from where he stood by Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island and prophetically wondered:

“What if these two locations changed places?”

The year was 1992. The novel that would come from that question, was Underworld.

If you have access to Google, then it’s not difficult to discover that the subject of this article lives in a certain tiny Westchester town that has no Black families and is “100 percent Christian.”

“Don DeLillo” and “Bronxville” yields 2,490 results in .30 seconds.

There’s an opinion piece by Journal News writer and Yonkers resident Phil Reisman, about the time that his “dog once lunged at Don DeLillo.” Recounting, “After that, whenever DeLillo saw us coming, he would furtively cross the road to the other side of the bridge.”

The town’s local and on-line paper The Daily Voice announces each year in bold headlines, “Happy Birthday to Bronxville’s Don DeLillo.”

And so on.

So, I’m not “breaking news” or spilling secrets here about where the man lives or that he’s reclusive-ish.

However, I am grateful that I get to teach the work of someone who is not a dead, White man. Someone who is a founding father of literary Postmodernism. Someone who has carved out a way - against all conceivable odds - to publish 28 books for a niche audience of intellectuals and poseurs (or both), and to win the hearts and minds of critics worldwide with literature that is not user-friendly, keeps one at arm’s length at all times, and forces its captives to live at the sentence-level.

That my students got to engage with “the Don” (but most definitely not “The Donald”) of Postmodernism (who was there at the Dawn of Postmodernism), is what the job of teaching should really be about. That it took DeLillo two weeks to respond to my students, but seven years to David Foster Wallace’s letter, really says something.

So much of what we teach in English classrooms across America is penned by pale, exalted ghosts: we’ve institutionalized Salinger and Dickens at the expense of nearly everyone else. There are tens of thousands of “working authors and artists” in this country who can be reached; they can engage with questions that only they can answer, providing definitive and certified “author intent” for the motivations behind novels, poems, short stories and even songs.

I made a final attempt to reconnect with Don DeLillo after he’d written me off as little more than an autograph hound [I’d asked him to sign yet another set of his books for an enthralled colleague].

He’d responded:

“I am getting out of the book signing business.”

Several years later I awoke one night in a fit of inspiration and wrote DeLillo one last letter.

It wasn’t a rhetorical exercise - but an attempt to pay him back for the kindness he’d shown my students - for the generosity of his walking across the street to sign a great many books on my behalf - and for his willingness to engage with a public high school teacher when his Rolodex is filled with the biggest publishing, film, theater and art- world players.

And his close friends are Salman Rushdie and Paul Auster.

Book world PR maven Carolyn Amussen had most likely meant something to DeLillo in the 1970s when he was trying to find his way through the thick smoke produced by the Manhattan literati. She had just passed away at the time of my letter. Her library was liquidated. I had stumbled upon the last available book from her estate for sale, and it wasn’t just any book: it was an association copy of a John Updike autobiography personally inscribed to Amussen. Updike had “book-reviewed” DeLillo (it wasn’t a flattering review of Cosmopolis, but it wasn’t a hit piece either). That her copy would end up on DeLillo’s bookshelf? The intersectionality of it all seemed too serendipitous to fail.

But it did.

No response came to what I wrote here:

“On May 3, 1971, (now approaching the 50th anniversary of the publication of Americana), HM & Co. publicity director Carolyn Amussen tried to do the impossible: to promote and market a debut novel printed in an edition of just about 5,000 copies, with a stark white dust jacket that has a meta-montage of images of a man with a camera (that feels like something torn right out of a John Berger art lecture co-taught by Antonioni), and a rear panel photo that tries not to be Mailer or Heller posturing for their first novels - but a quiet, reflective, young Martin Sheen-type who is as sensitive and considered in his sentence constructions as he is in his world view (and that his persona, if anything, won't be the swashbuckling Mailer, or the deadpan Heller, but the philosopher-poet).

Carolyn knew, better than anyone, that selling a book was "all about the blurb." And Joyce Carol Oates offered up a truth about you - that you are "a man of frightening perception." You'd later tell the world of appliances replacing family members in White Noise, and (most recently) what that overreliance on technology has cost us (in The Silence). Oates' stamp of approval might not have helped sales of Americana - or End Zone - as what Carolyn couldn't have known 50 years ago is that you would defy any label or genre, and that your words would speak (terrifyingly) for themselves.

In my American Literature course, I begin each year with "Midnight in Dostoevsky" as a cautionary tale about the battle (for dominance) of the hard-and-soft sciences.

The enclosed copy of John Updike’s memoir Self-Consciousness, inscribed to Carolyn, is the last intrusion into your personal life I'll make. If you ever have the desire to see how high school students react to your work (I also use White Noise in the course as you may remember), please "stop in" for a Zoom to help them (and me) navigate your work (which I think I get on an intuitive level, but that's about it, so I apologize for my basic understanding of what you do on paper; I will tell you that your syntax and diction, and your pop-culture infusions speak to me like nothing else). It doesn't matter when that hypothetical visit might happen in the year. The virtual door is always open...until, of course, someone severs it.”

And, in all likelihood, this is the cutting of that cord.

*Select details have been changed for opacity’s sake. Everything else is as it happened.

Author’s note: DeLillo sold his Bronxville home on June 24, 2022.